|

HOW ONE WRITER FOUND HIS PASSAGE TO EDEN - VIA A FULBRIGHT GRANT Like many journalists I have met, I'd always wanted to travel overseas. I knew that for someone interested in science and ecology like myself, traveling abroad would be a wonderful opportunity to research articles about a new environment, see exotic wildlife, learn about a different culture, and gain fresh perspectives on the way we run our national parks and environmental policies in the United States. But how to do this, especially on the slender income of a master's student at New York University's Science and Environmental Reporting Program? Grants were available, but most applications required a proposal for a specific writing project. Like pitching an article to an editor, the key to winning a grant was a well thought-out idea. But what topic and which foundation? My choice of topic came serendipitously. To help pay for tuition, I worked part-time as a photo editor at an advertising studio located on the city's all-too-colorful Bowery. Every now and then, my boss would invite some of his cronies over for a few beers and cigars, and they would sit around and show us slides from their latest work. One day, a famous underwater photographer from National Geographic dropped in, fresh from an extended visit to the Antipodes. His pictures of a place called Lord Howe Island were breathtaking to me - made all the more so by the fact that I had just finished clearing away empty winebottles and a dead rat from the front stoop of the boss's graffiti-encrusted building. The underwater photographer raved about his amazing experiences on this sub-tropical Australian national park 391 miles out in the South Pacific, whose 350 citizens had banded together to protect endangered native birds and marine life. Wildlife restoration programs were funded with proceeds from the island's harvest of palm nuts. I thought to myself, "This guy should know something about islands -- he's been taking underwater photos for 30 years." Maybe this experiment in environmental protection was the stuff of a grant proposal. I went to the Australian consulate in Rockefeller Center and began to read up about this island and other Australian parks in their library.

"A year ago I was researching toxic waste sites in Queens", I thought to myself. "I wouldn't be here if it wasn't for that Fulbright Postgraduate Traveling Fellowship." The Fulbright program was started at the end of World War II, as a way to promote peace through the mutual exchange of citizens. In setting up the program, Senator J. William Fulbright drew upon his own youthful experience as a Rhodes scholar at Oxford University, England; he once said "The best way to appreciate another's viewpoints, their beliefs, the way they think, and the way they do things is to interact with them directly on an individual basis -- work with them, live with them, teach with them, learn with them and learn from them." Or, as he wrote in his autobiography, "It is hard to shoot someone you know." Since 1946, more than 70,000 Americans and 130,000 foreigners have participated from 130 countries. Illustrious Fulbrighters include composer Philip Glass, actor Stacy Keach, scientist Nancy Wexler, novelist John Updike, and former Secretary General of the United Nations Boutros Boutros-Ghali. The program offers several different scholarships under its umbrella, including teacher-exchange programs, grants to give or attend seminars (the Senior Scholar program) and funds to cover solely the costs of overseas travel. Out of all the Fulbrights, the Full Grants, also known as Postgraduate Traveling Fellowships, are most in demand. They provide for everything from round-trip airfare to health and accident insurance. In all cases, the choice of research topics is open to whatever interests the applicant; in Australia this past year, American postgraduate fellows looked at everything from the diet of brushtail possums to the implications of Aboriginal land claims. Application forms are available at most universities, or by writing the foundation's headquarters at the Institute of International Education (IIE) at 809 UN Plaza, New York, NY 10017. Applicants don't have to be affiliated with academia to apply, although it can a plus, as many institutions maintain a database of old applications that were successful. These can give an idea of the structure of a winning grant. Schools also sometimes have scholarship advisors who can help you prepare for the interviews. At NYU, Dean Robin Nagle helped us get over our jitters. I'll never forget one bit of advice she gave - when interview time arrives, commented Nagle, "Don't wear too much cologne." She said nervous applicants sometimes went overboard with the colognes and perfumes; by the end of the day, the review committee was gasping for breath. If you don't have the help of a university advisor, you can still get the benefit of such preparatory sessions by attending workshops on navigating the application procedure, given to prospective applicants by the IIE. These are usually administered by the organization's Walter Johnson. After years of handling applications, he's seen it all. "Applicants can be too clever for their own good," Johnson says, citing the time someone used a photocopier to shrink their proposal to fit the maximum allowed size - with the resulting type so tiny it was unreadable. Johnson and others recommend a few steps to up the chances of acceptance:

Nagle said that evaluators favor applicants who have a connection to an academic institution in the host country. "A letter of affiliation is one of the best ways to have a proposal stand out," she said. Getting such a letter is daunting but not impossible; I did it all over the internet. I found promising leads in my field by downloading course catalogs from Australia, then tracked down the person in charge and e-mailed a resume and a description of my project. Eventually, I struck up a rapport with a faculty member who mailed a four-sentence letter saying he would oversee my work. (It all would have been difficult without e-mail: airmail takes two weeks to reach the land down under, while surface mail takes three months.)

When it came time to write my application, I had a list of places I wanted to visit, and reasons why I felt they were important. I wanted to experience Australia's national parks firsthand and observe their conservation efforts in order to see what America can learn from the Australian experience. I had a personal interest in the topic as well -- as a college student, I'd worked as a seasonal employee and part-time volunteer at Yellowstone, the world's first national park. Besides Lord Howe, I was attracted to Shark Bay, where the park concept is taken one step further, and wild dolphins interact with human beings. It's unlike a traditional preserve or zoo; as a ranger later told me, "We have to use our common sense and make it up as we go along." Or, as the manager of a local tourist development put it: "There's a lot of money riding on the back of those fish."

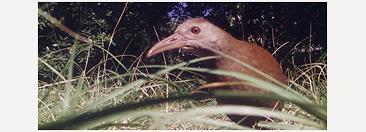

In my encounters with Australian culture, I also had some lively pub discussions about freedom of the press -- Australia does not have a First Amendment or Bill of Rights, and I have actually met law students who laugh at such notions. (Needless to say, as someone who lives and dies by the First Amendment, I felt differently. I found myself quoting passages from old Journalism 101 textbooks to clear up factual errors and misconceptions.) Figuring out how to use my time most effectively was also tricky. Was it better to spend every moment researching stories now, and then write them up later when I returned home after a year? Or write things as they occurred? I finally chose the latter, with the emphasis on taking the time to experience as much as possible. It seems to have been the right choice: since arriving here, I learned how to make a traditional boomerang from an Aboriginal elder, swam with dolphins, fell in love, flew with the Royal Flying Doctor Service, fell out of love, and discovered the safest way to hold a miniature kangaroo without getting hurt (by the tail, upside-down, at arm's length). I wrote for publications such as Science, Scientific American, and Newsday on subjects ranging from the social life of dolphins to the search for the last Tasmanian tiger to stolen dinosaur fossil tracks. Of course, not all is gravy. I've been bitten by poisonous spiders and stalked by cassowaries - 6-foot high birds that look like escapees from "Jurassic Park" and leap into the air to disembowel their prey with their claws. The 16-hour time zone difference between this part of Australia and the east coast of the United States makes calling people back home horrific, and this "tyranny of distance" - as one Australian sociologist calls it - means that it's easy for editors to ignore you. Publisher's checks can take months to arrive from the US, and as much five weeks to clear the Australian bank. This makes budgeting a fiasco, although some editors have been kind enough to have their accounting departments send checks by electronic transfer. But the chance to do interesting articles makes up for some of this. Things were so interesting, in fact, that I requested an extension on my visa after my grant expired in order to stay longer and cover more stories. (My parents are starting to ask if I will ever come back.) I feel like I cannot leave until I have been to the northern tropics, and down to the Great Barrier Reef - but I suppose that no matter how long you stay in a foreign country, you always want to see just one more place. And there is something very appealing about being able to call yourself a "foreign correspondent" - and get clips with datelines saying "Tasmania." As for Lord Howe, excerpts from the material I gathered have appeared in everything from a chemistry journal to the Boston Globe. I'm still awaiting word about my doing an extended essay on this unique national park, but at press time, Australian Geographic was considering it. When friends and colleagues ask if I thought the Fulbright was worth the effort, I say "Absolutely. " The only problem is that once you get the travel bug, you keep wanting more: I've noticed that when I do finally go back to the States, my return flight has to pass through Indo-China, and the ticket allows me to make four stopovers for as long as a year . . . — Dan Drollette was a 1993 recipient of a Nate Haseltine/Council for the Advancement of Science Writing scholarship. Portions of this article are reprinted from Columbia University's 21stC magazine. |

from the Fall 1997 issue of "Science Writers," the newsletter of the National Association of Science Writers |

Two years later, I found myself sitting in a cottage next to the Lord Howe Island lagoon, listening to outback guide Ray Shick give hints about local bushcraft while a passing tropical squall drummed upon the tin roof. Ray was a fount of information about life on this pristine, Manhattan-sized isle and the effort to protect it from large-scale development. ("We were greenies before anyone else," said the daughter of the proprietor of a nearby lodge.) After an afternoon spent listening to tales of island men lost at sea and the secrets of harvesting Kentia palm nuts - Howea forsteriana seedlings are the island's major export - I headed to my bicycle. Through the palm fronds and banksia flowers I could see the surf crashing into the sides of 2,887-foot tall Mount Gower.

Two years later, I found myself sitting in a cottage next to the Lord Howe Island lagoon, listening to outback guide Ray Shick give hints about local bushcraft while a passing tropical squall drummed upon the tin roof. Ray was a fount of information about life on this pristine, Manhattan-sized isle and the effort to protect it from large-scale development. ("We were greenies before anyone else," said the daughter of the proprietor of a nearby lodge.) After an afternoon spent listening to tales of island men lost at sea and the secrets of harvesting Kentia palm nuts - Howea forsteriana seedlings are the island's major export - I headed to my bicycle. Through the palm fronds and banksia flowers I could see the surf crashing into the sides of 2,887-foot tall Mount Gower. Upon arrival in the land down under, I felt like I had stepped into a world of mirror-images. Everything is reversed: people drive on the opposite side of the road, light-switches flick down to turn on, swans are black, and ski season is in July. Luckily, the people speak English -- of a sort. The Aussies' rhyming slang is almost impenetrable to the newcomer: your best friend is sometimes called your "China plate," as "plate" rhymes with "mate." And I had to buy an Australian-English dictionary to decipher the newspapers, in which words such as "rort" and "twee" appear with distressing regularity. (Rort: to trick or scheme. Twee: excessively dainty.) At least now I can watch movies like "Muriel's Wedding" or "Shine" and catch all the inside jokes.

Upon arrival in the land down under, I felt like I had stepped into a world of mirror-images. Everything is reversed: people drive on the opposite side of the road, light-switches flick down to turn on, swans are black, and ski season is in July. Luckily, the people speak English -- of a sort. The Aussies' rhyming slang is almost impenetrable to the newcomer: your best friend is sometimes called your "China plate," as "plate" rhymes with "mate." And I had to buy an Australian-English dictionary to decipher the newspapers, in which words such as "rort" and "twee" appear with distressing regularity. (Rort: to trick or scheme. Twee: excessively dainty.) At least now I can watch movies like "Muriel's Wedding" or "Shine" and catch all the inside jokes.